(KTSG Online) – Starting this year, around 150 major emitters, accounting for 40% of Vietnam’s total carbon emissions, have entered the compliance phase of the carbon market. Once emission allowances are allocated and assigned market value, CO₂ becomes a new financial cost, directly affecting corporate business performance.

CO₂ enters corporate accounting books

Vietnam’s carbon market roadmap stipulates that the first compliance period begins on January 1, 2025. Approximately 150 facilities with the highest emissions will be allocated emission allowances for the 2025–2026 period. These entities mainly operate in thermal power, cement, steel, chemicals, and oil refining. Targeting the largest emitters aims to ensure stable market operations before expanding to roughly 1,000 enterprises after 2028.

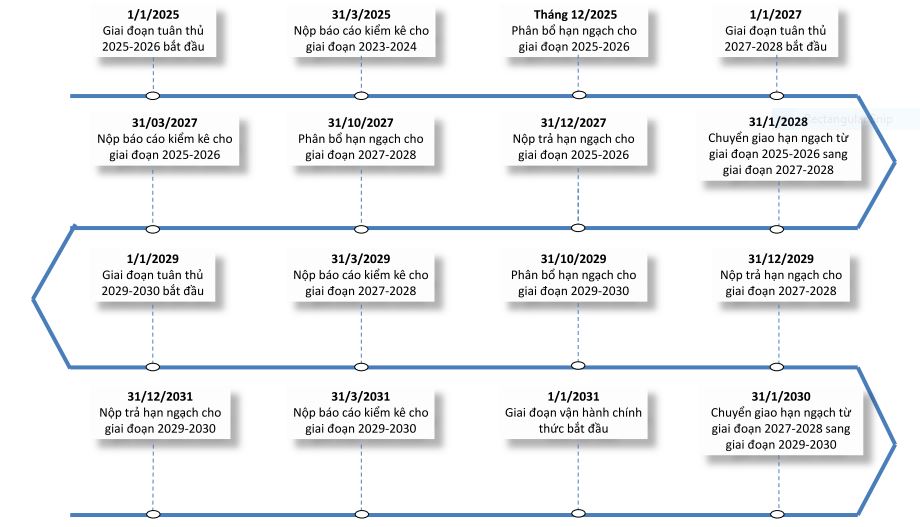

Roadmap for emission inventory, allowance trading, and transactions. Source: Department of Climate Change

Once allowances become tradable commodities, companies must treat CO₂ as either a financial asset or a financial liability. If emissions exceed allocated limits, enterprises must purchase allowances on the exchange. If emissions are lower, surplus allowances become assets that can be sold to generate cash flow. Allowance prices fluctuate based on supply and demand, forcing companies to budget for CO₂ the same way they budget for raw materials or energy.

Under international accounting practices, emission allowances are often recognized as intangible assets or special inventory. When applied to corporate accounting systems, key questions arise around recognition, revaluation, and price volatility risk management on financial statements. As a result, chief financial officers are no longer managing only capital costs, but also carbon costs.

Financial Risks Emerge When CO₂ Has a Price

Pricing carbon introduces multiple financial risks. Allowance price risk is the most significant. Scarcity-driven price increases can inflate production costs and erode profit margins. Export-oriented enterprises with long-term contracts are particularly vulnerable, as carbon costs cannot easily be passed on to customers. Steel, cement, and chemical sectors face dual pressure from both Vietnam’s domestic Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

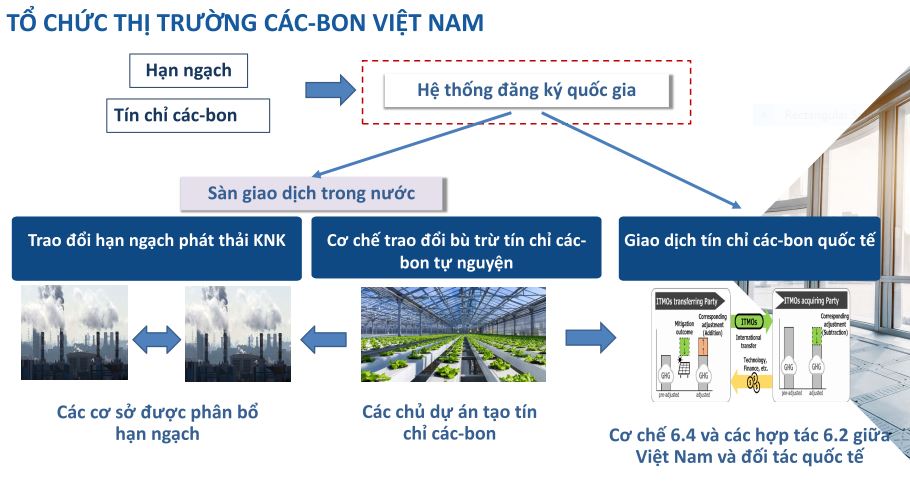

Source: Department of Climate Change

If an enterprise anticipates emissions exceeding its allocation, it must purchase additional allowances at the end of the compliance period—especially problematic if market prices are high or expected to rise. According to accounting standards, companies must recognize a provision for this liability in advance.

For example, during the 2025–2026 period, an enterprise receives 100,000 tons of CO₂ allowances but forecasts emissions of 130,000 tons, resulting in a 30,000-ton shortfall. If the current market price is VND 350,000 per ton, the company must immediately record a provision of VND 10.5 billion for the expected purchase obligation—without waiting for the actual transaction.

Provisioning risk is another concern. If allowance prices decline or inventories lose value, companies must recognize impairment losses, directly affecting net profit and dividend capacity.

For instance, a company purchases 10,000 tons of CO₂ allowances at VND 300,000 per ton, recording a book value of VND 3 billion. Six months later, the market price falls to VND 200,000 per ton, forcing the company to record a VND 1 billion impairment loss, booked directly as an expense—similar to inventory write-downs.

When the cost of purchasing allowances exceeds the cost of internal emission reduction, enterprises are eventually compelled to invest in energy-efficient equipment, process optimization, or electrification. Buying allowances is a short-term fix; emission reduction is the only sustainable strategy.

Allowance allocation is based on MRV data (Measurement, Reporting, and Verification). Without accurate measurement systems, allocated allowances may not reflect actual emissions. Poor data increases the risk of penalties, under-reporting, or forced purchases at high prices.

From Compliance Cost to Green Asset Opportunities

Emission allowances are not only a source of cost or risk—they also create opportunities. Companies with clean technologies may generate surplus allowances for sale, creating new revenue streams beyond core operations. Emission reduction projects meeting international standards can generate carbon credits, particularly in methane capture, waste-to-energy, energy efficiency, or circular economy projects.

When Vietnam’s carbon exchange becomes operational—expected next year—allowances will have listed prices, volatility, and liquidity, forming a new class of green assets in the economy. For enterprises, this represents both a compliance cost and a supplementary financial market if emissions are kept below allocated levels.

Vietnam is also preparing to participate in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Enterprises implementing internationally certified emission reduction projects may trade credits on global markets at prices 5–10 times higher than domestic voluntary markets. For example, one ton of CO₂ priced at USD 5 domestically could fetch USD 50–70 internationally—an opportunity to attract green capital and large-scale bilateral cooperation.

Data Capability and Emission Reduction Will Decide the Game

The Department of Climate Change under the Ministry of Agriculture and Environment—the authority responsible for allocating carbon allowances in the mandatory market—emphasizes that enterprises must complete greenhouse gas inventories and build reliable emission measurement systems. Without credible data, companies cannot accurately assess emissions, allowance needs, or potential surpluses.

Large-capacity cement plants, typically high emitters, will be subject to emission quotas this year. Photo: ximang.vn

Second, enterprises must integrate carbon costs into financial models, developing internal emission reduction plans and CO₂ budgets alongside capital budgets. Once CO₂ carries a price, every business activity must account for associated emissions.

Third, companies should assess their ability to generate carbon credits or surplus allowances. Done well, CO₂ shifts from a cost burden to a revenue source. Cleaner enterprises gain competitive advantages and become more attractive to investors and customers.

This year marks the first time CO₂ officially becomes a financial cost for Vietnamese enterprises. The entry of roughly 150 major emitters into the compliance phase sets the stage for Vietnam’s domestic carbon market. This presents both pressure and opportunity: those who prepare early can turn allowances into assets and competitive advantages; those who lag will pay through shrinking margins and rising production costs.

From now on, CO₂ is no longer confined to environmental reports—it sits on the balance sheet.

Four Operating Principles of Vietnam’s Carbon Market

(Source: Department of Climate Change)

-

Enterprises must surrender emission allowances based on greenhouse gas inventory results for the 2025–2026 period.

-

Enterprises may borrow up to 15% of allowances from the next compliance period to fulfill obligations.

-

Surplus allowances may be carried forward to the next period after full compliance.

-

Carbon credits may be used for offsetting, capped at 30% of allocated allowances.

Source: thesaigontimes.vn